Source: http://readnow.isentia.com/ReadNow.aspx?2Lemohy1d9Hl

Courtesy, compassion, community spirit: Catriona Rowntree explains how her country-raised dad helped her to flourish in the wider world.

Catriona Rowntree has criss-crossed the globe as a travel reporter for almost two decades. When she’s not travelling or designing her range of baby clothes, she’s enjoying farm life as a wife and mother of two lively young boys.

Whatever she does, she’s guided by memories of her father, Stephen Rowntree, who left her with firm ideas about the way life should be lived.

The best piece of advice that my dad ever gave me is that there are two types of people in life: the “gunnas” and the “doers”, and that I should always aim to be among the latter. Not those who are always “gunna” do this and “gunna” do that, but one of those who are always doing this and that.

His advice may have come from his childhood growing up in rural NSW.

He hailed from Quirindi, in the state’s north-west, and I think that being a boy from the bush gifted him with the most beautiful outlook on life. This included placing great value on authenticity and family, and taking pride in the way he conducted himself throughout his life.

I suppose one of the greatest gifts both my father and mother offered to their four children was the daily example of parents who were in love, who spoke to each other respectfully, who were courteous to each other and who put their family first. I did not grow up in a household full of arguments, even though there were a lot of people – not to mention the family pets – all living under one roof.

In our home on Sydney’s north shore, there were very clear rules. I am the youngest of four, and I watched my older siblings make a few more errors than I dared to. There was a code of conduct – my father was very clear that we should dress well and be respectful to adults. My dad was strict, but I could still turn to him more than to my mother for a compassionate and understanding response, and I always wanted to make him proud of me.

As the youngest child, you often feel that you don’t get heard. My brother had the Gatsby syndrome – everything he touched before the age of 21 turned to gold; he was brilliant at everything – and my sisters were creative and beautiful.

I quickly realised I had to figure out a way to show my dad that I was trying to make him proud of me.

We never had pressure put on us to fulfil a certain educational path. The directive was “do what makes you

happy”, but I always tried, through my career path and personal life and other choices, to do things that my dad would be proud of.

There was never a particular moment when I felt he was more proud of me than at any other time, but soon after getting into television, I noticed that Dad was quietly keeping a scrapbook of my press clippings – this was something that my other siblings teased him about.

Initially I was a bit embarrassed, but now I realise that it was an incredible source of pride for him.

When my father passed away in 2013, we were all overcome with grief, and my sister-in-law, who is a lawyer, tried to do what she could to help, so she went to his office and put all of his paperwork in order. She gave me a box of clippings documenting my life Dad had kept, from the cover of The Australian Women’s Weekly to a tiny mention in a community paper. To me, it was a sign that he’d been quietly supporting me for years, without the need to be boastful or show off to anyone else.

My dad believed, until his final hours, that he would beat cancer – his positive outlook never wavered. So, even though he’d had cancer for a while, it was a genuine shock when he died.

Stress can be harmful to every one of us. I’ve learnt to be mindful of that obviously a positive outlook is important.

But a tiny little detail I value from my father’s passing is the importance of letting the people who you love know that; and to be able to verbalise it. The last words my dad and I shared together when he was in hospital were, “I love you.” I have so much peace in knowing we were able to express that.

Something that also made me proud was the outpouring of love so many others had for my father. One of his incredible legacies was the time he’d given to his local sporting club.

My brother was a very good rugby union player – he played for Sydney University Football Club – and at a time when the team was struggling, my father put his hand up to help.

Dad was like a second father to many young players who’d grown up outside Sydney and had left their families to play sport. So often on a Saturday, I’d wish he was at home, mowing the lawn – but he was always helping others.

That’s something I have taken on as much as I possibly can – volunteering my time where possible.

Dad did this for more than 20 years, and today Sydney Uni Football Club has a special day to celebrate his volunteer spirit and present an annual award to the individual who has most volunteered their time. I take Dad’s grandchildren to this event (we drive there in his old car) because I think we need to be conscious of the legacy we will leave. Dad’s legacy is unbelievably positive.

Dad was from a long line of people with a strong sense of community. My great-great-great-grandfather was a sea captain who brought the first paying customers to Australia, and he ended up being what is literally called a “man of mark” in Sydney – one who helped to establish many wonderful things with the creation of the new city at the time.

His children ultimately ended up living in the country and always being involved in their local community – so maybe it’s something that is in the DNA.

Another thing I inherited from my dad: neither of us could stop talking.

But I never heard him swear. Having gone into live radio and television, I’m grateful I grew up in a household where we weren’t allowed to swear, because that could ruin a career in a heartbeat.

I think it’s really interesting that I was raised by a father who felt very strongly about the way we present ourselves and believed we should treat others in the same manner we expect to be treated.

I spent most of my career at Channel 9 and my boss there, Kerry Packer, shared a similar ethos. It’s allowed me to have longevity in my career.

I definitely see a strength of character in my boys that I would like to think would make their grandfather proud.

Ra-ra, they would call him.

My siblings and I – all four of us went to private schools, a major task for any parent. I cannot remember a time that my father didn’t have two jobs.

When I was 12, my father sat me down, showed me how to write a thankyou note, and insisted I write them wherever possible. When he went away on rugby tours, he would always buy me beautiful writing paper. To this day, I always write a personal note of thanks.

A little gift that my father gave to each of his children when we left school was a small amount of money, about $1500. He said, “You can do with this whatever you like, so long as it will benefit your lives.” My sister put it towards an around-theworld ticket, my brother put it towards a car. I used it to help pay for a diploma course in journalism.

For many years, I’ve been asked to be an Australia Day Ambassador and Dad would often come with me to some of the out-of-the-way places I was asked to go. One of his proudest moments was when I was asked to be the Australia Day Ambassador to his home town of Quirindi, and we had our photos taken under the Rowntree’s Lane signpost.

I’m very proud of my family history, so it was important to me to retain my family name when I married. I know Dad was equally proud about that. My husband respected that, too. I want my children to be appreciative of what their relatives have done to help others and to understand how that history has helped give them the life they live today.

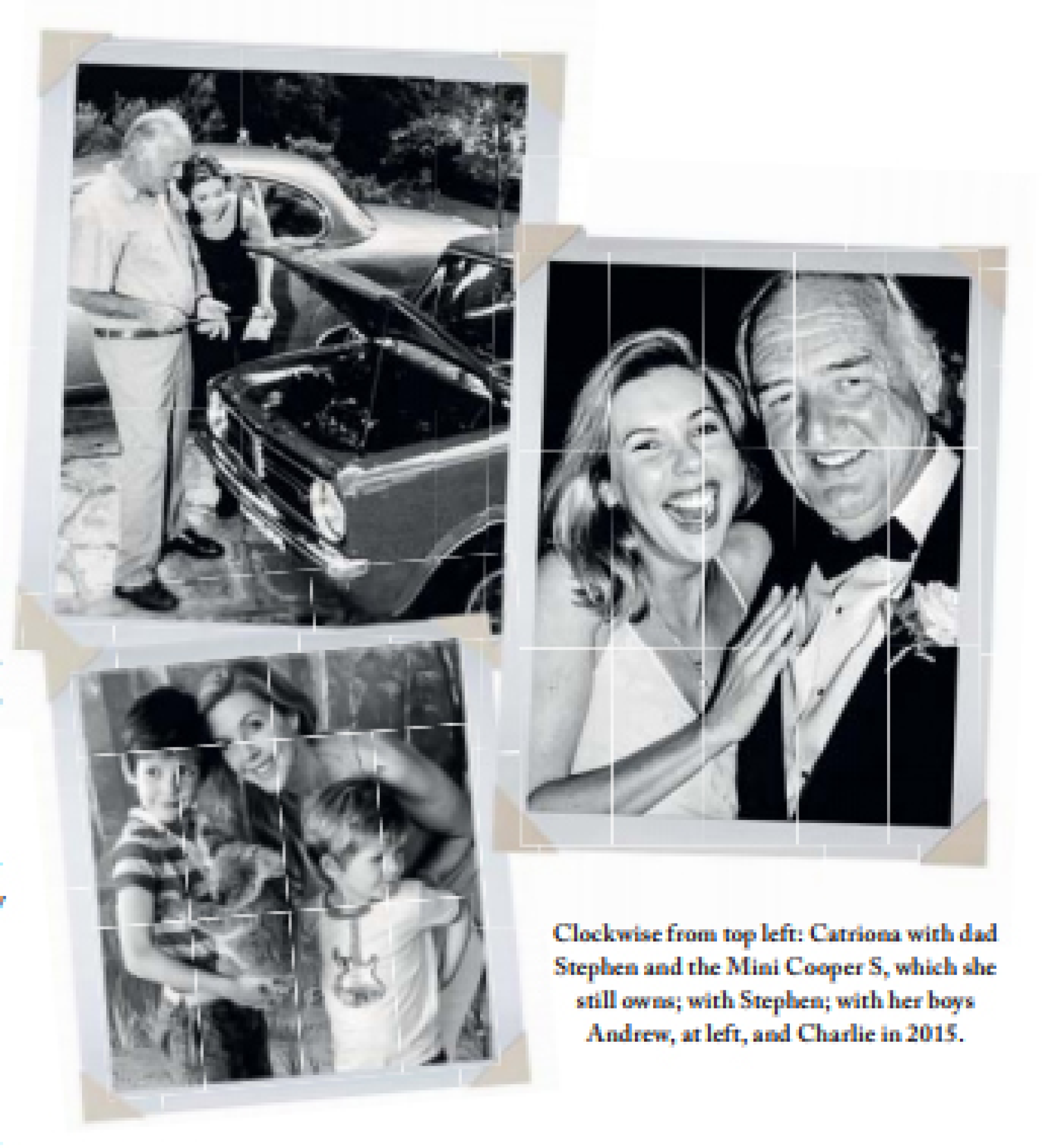

There are not enough pages here to talk about all the things Dad did for fun. He was a wonderful example of work-life balance. He had an absolute passion for most things with a motor, so he would take all of us to car shows and boat shows, and he loved to tinker with beautiful old cars as well.

I inherited his beautiful vintage Jag that we worked on together. He helped me buy my first car, a vintage Mini, which I still have.

You know that expression about how you can take the boy out of the country but you can’t take the country out of the boy? I think it’s interesting that my father grew up in the country, but then fell in love with a north shore girl and thought, “This is where I’m going to raise my family” – yet two of his children have ended up back on the land. I found myself marrying a farmer, and living and raising my children in the country.

What do I miss most about my father?

I suppose just having that one person I could call at any time of the day my quiet little cheer squad.

Dad wasn’t perfect. But, ultimately, all I can say is that in my father’s final moments, he was surrounded by love, and no one could say a bad word about him.

He did his best for his family, and was rewarded with bucket-loads of love. Edited extract from Things My Father Taught Me, edited by Claire Halliday (Echo Publishing, $30), out now.

“A TINY LITTLE DETAIL I VALUE FROM MY FATHER’S PASSING IS THE IMPORTANCE OF LETTING THE PEOPLE WHO YOU LOVE KNOW THAT. “